Tweeting the killing of Bin Laden

Note: This was originally posted on my personal blog, but I thought it was worth sharing with We Are Social’s audience as well

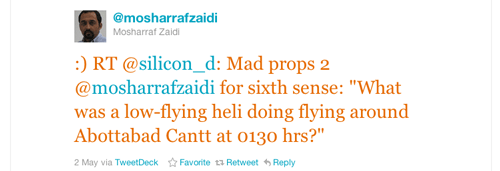

As the biggest news story of the week, the killing of Osama bin Laden, broke, I was on holiday in New York. As the clock ticked passed midnight local time (EDT) on Sunday night, my girlfriend Maha, sitting next to me on the sofa, passed me her Blackberry and showed me a retweet of curious remark related to the events unfolding. A Pakistani journalist, Mosharraf Zaidi, reminded his followers how he had earlier remarked:

The television news we were watching had nothing new to show by now, and was resorting to reruns of President Obama’s address earlier. So, with my curiosity piqued, I started looking up to see if there had been any coverage of helicopters in Abbottabad earlier that day. Googling around normally found the odd news report about a possible training accident, but very little of substance or interest. So I turned to searching Twitter, specifically with Google Realtime, which allows you to exclude Tweets from before or after a certain time of day. This was important, as once President Obama had disclosed the location, Twitter exploded with mentions of it and it became impossible for ordinary Twitter search to cope.

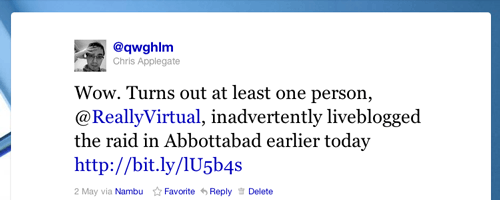

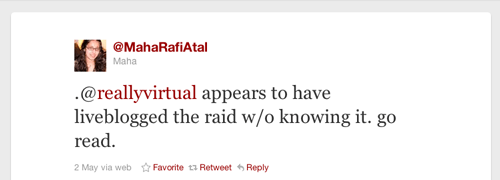

With anything after 11pm Eastern Time excluded, I was able to find Tweets by a guy called Sohaib Athar, or @ReallyVirtual. Once I clicked through to his timeline, I found out he had actually liveblogged the entire raid, unaware that it was America seeking its public enemy number one. At 12.38am, I tweeted, and Maha tweeted too:

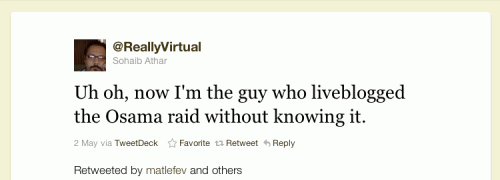

And then at 12.41, three minutes later, Sohaib tweeted the defining moment of the story:

By the next morning, Sohaib was one of the most famous Twitterers around, being interviewed on television and getting mentioned in most mainstream media outlets. His follower count shot up from 750 to just over 100,000 as of today.

Steve Myers of the Poynter Institute got interested in how the story spread and did some investigating (including talking to me and Maha), producing a phenomenal forensic blog post – and from his investigation it appears that mine & Maha’s Tweets were one of the first ones to mention him and may have broken the story.

Caveat: I say may – correlation does not imply causation. I looked on Google Realtime for earlier Tweets from anyone linking to his account pointing and highlighting his liveblogging, and could not find any, but that doesn’t mean there weren’t any. Nor am I trying to take too much credit for breaking the story – had I not tweeted about him, someone else would have found him sooner or later – the tools were there, and reasonably well known in the trade (and if you work in the media and don’t know them, then for God’s sake learn them).

Steve’s piece is a great bit of detective work and social network theory in one, and I’d like to pick up on a few points he made. Firstly, he states “the number of followers doesn’t matter as much as who those followers are” – this is a really interesting one and worth elaborating. I have about 3,300 followers on Twitter, but most of those are UK-based and would have been fast asleep. Maha has 1,300 followers, but she is a journalist based in the US, specialising in amongst other things, Pakistan. Her following, while smaller, is full of journalists, policy people and those with an interest in Pakistan and the wider region; these would be the exact kind of people to pick up on the significance straight away.

The numbers then don’t always count. But what definitely does count is the story. Steve picks up on the role I played bridging different social networks (in a paragraph that makes me feel odd, being referred to by my surname…):

Applegate was a bridge too, in a slightly different way. He added essential information that resonated with people and spurred them to pass it on.

I didn’t regard myself as a bridge at the time. I just thought, and tweeted: “Wow”. But then as it unfolded more it became clear that the unwitting Tweeting was a central factor in the story. Abbottabad is a relatively quiet town, populated by retired generals and known for its schools and universities (not to mention their military academy). Sohaib himself had moved there to get away from the much more dangerous and turbulent Lahore to find quieter climes – his Twitter bio states he is “an IT consultant taking a break from the rat-race by hiding in the mountains with his laptops.”

Given a popular narrative of Bin Laden hiding in caves and the like, to find out he was living in a mansion somewhere so quiet, so genteel and so near to the heart of the establishment came as a surprise. The key thing that made Sohaib’s liveblogging from earlier in the day so compelling was that it was completely unwitting, mirroring our own disbelief that Bin Laden had been quietly residing in the Pakistani equivalent of Tunbridge Wells all these years, without any of us knowing. The story chimed perfectly with our own emotions. And because the story had been unwitting, it was also candid and honest, cutting through the hype and speculation that the 24-hour news stations were resorting to.

Finally, the whole episode shows how transformative Twitter can be. As the story matured and his fame rose, Sohaib took on the role of citizen journalist, becoming a correspondent of sorts (not many other residents of Abbottabad are on Twitter, he remarked, it’s mostly Facebook). He conducted interviews on television, and ventured out into town to take photographs and report back on the mood in the town.

This is a far cry from the cynical caricature of Twitter as an echo chamber – a place where nothing new is said and everything is relentlessly retweeted. As the story progressed, Sohaib came to the wider community’s attention and it in turned shaped his role in the affair. His relationship with Twitter evolved – it went from being a place to remark on the events that had taken place, to realising their significance, to realising his own significance, and then finally embracing it with intrepidness, intelligence and good humour. I might have been one small factor that sparked the process off, but I definitely can’t take any credit for the phenomenon he has become – that’s entirely to his own credit, and something that we should celebrate.